International finance through the lens of BIS statistics: the global reach of currencies

The use of key currencies in international finance far outstrips the issuing jurisdictions’ share in global economic activity. The US dollar dominates globally, while the euro, yen and pound sterling have a smaller international footprint. The reach of key currencies becomes apparent only in statistics with a currency dimension. The BIS statistics on international banking, bonds and derivatives markets have had a currency dimension since their inception. This dimension is essential for assessing exposure to currency risk, squeezes in funding markets and vulnerabilities associated with foreign exchange markets.

Why are some currencies widely used in the international domain?

Factors cited in the literature include (i) the weight of the issuing country in global trade and finance; (ii) the availability of safe assets denominated in the currency, with deep and liquid markets; (iii) stability based on sound fiscal and monetary policies; and (iv) exchange rate flexibility and a convertible capital account to accommodate capital flows.3 Currencies that score high on these factors tend to have liquid government bond markets that serve as a basis for pricing other assets in that currency. Network effects in the adoption and use of a currency in trade and finance then tend to reinforce each other.

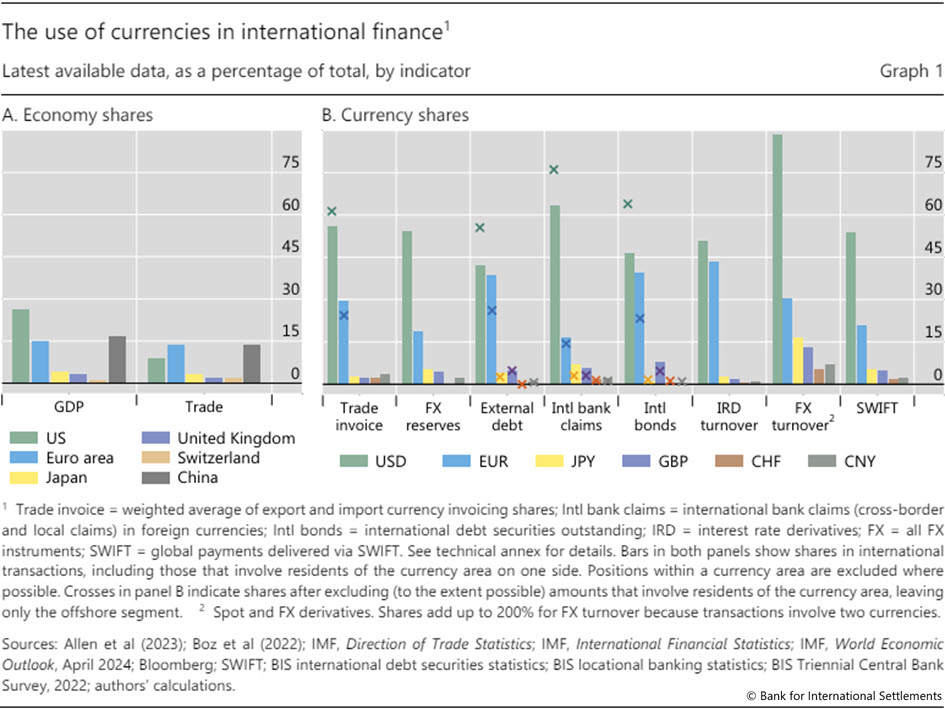

Several major currencies fulfil these conditions, yet one currency – the US dollar – has been dominant in the post-World War II era. Graph 1.B presents currency shares in international activity (bars) and offshore activity (crosses) across several markets.4 While the euro, yen and other currencies do play an international role, the US dollar occupies the top position in all markets (Graph 1.B, green bars). Trade invoicing in dollars begets dollar debt that needs to be financed. The depth of dollar capital markets creates thick market externalities that attract both investors and issuers.

Focusing on offshore activity puts the dominance of the dollar into even sharper relief (Graph 1.B, green crosses). The shares of the dollar in each market shown, and of the euro in all but one market, outstrip the issuing jurisdiction’s share in global gross domestic product (GDP) (Graph 1.A). By contrast, the shares of the British pound, Japanese yen and Swiss franc exceed in only some markets the corresponding GDP shares. The use of the renminbi, which is not fully convertible, presently falls short of China’s weight in the global economy.

International banking

Deposits of US dollars began to accumulate in banks outside the United States in the late 1950s, giving rise to concerns over their impact on the transmission of US monetary policy at a time when policy frameworks focused on control of monetary aggregates. This led to the collection, in the 1960s, of the BIS LBS, to track banks’ international claims5 – the complement to domestic monetary aggregates. The LBS have since been expanded to capture how key currencies are used in international banking across countries and sectors.

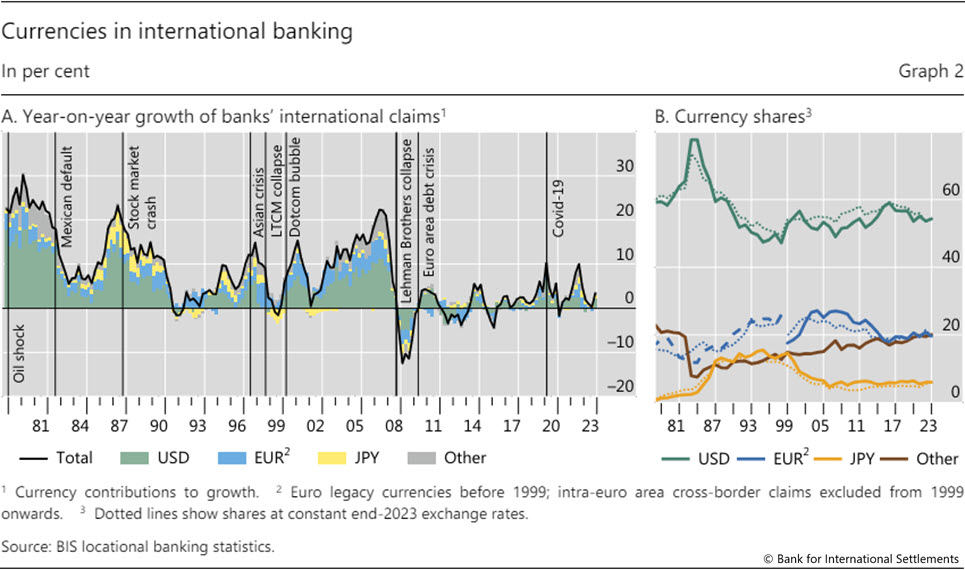

The boom-bust cycle in banks’ international claims largely reflects dollar flows, given the dollar’s outsize role in international banking (Graph 2.A). In the three decades before the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), claims grew by more than 10% per year on average, but with considerable variation around crisis events (vertical lines). Variation in dollar claims accounted for most of this. Claims growth collapsed after the GFC and has been subdued since, as banks restructured their balance sheets and non-bank financial institutions gained ground in international finance.

The dollar’s share in banks’ international claims peaked at almost 80% in the mid-1980s, after which it gradually lost ground (Graph 2.B). Yen claims gained share in the late 1980s, when Japanese banks expanded their global footprint amidst a domestic banking boom. Similarly, claims denominated in European currencies grew ahead of the introduction of the euro in 1999. And euro-denominated international claims rose rapidly after the currency’s launch, propelling the euro’s share to around 25% in the mid-2000s. It subsequently retreated in the wake of the euro area sovereign debt crisis of 2010–12, yielding ground back to the dollar.

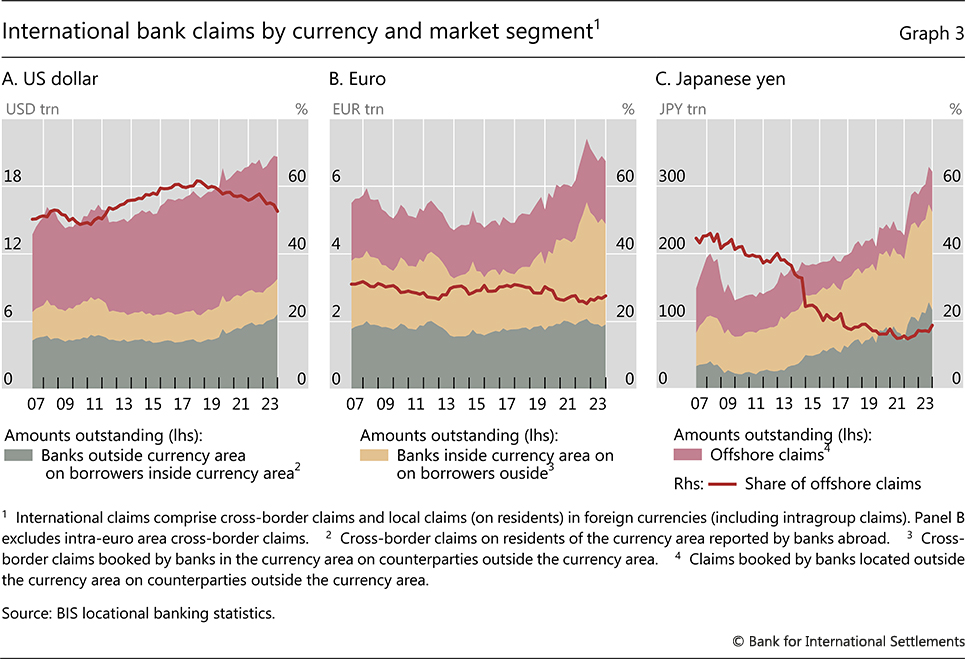

The offshore use of the US dollar underpins its dominance in international banking. Traditional international banking typically involved cross-border positions in the domestic currency of either the lender or the borrower – for example, a dollar loan from a bank in the United States to a borrower abroad (Graph 3.A, tan area), or a dollar loan from a bank in Europe to a borrower in the United States (grey area). However, more significant for the dollar is the offshore segment (red area), ie dollar positions that do not involve residents of the United States (McCauley et al (2021)). Offshore dollar claims peaked at two thirds of total dollar claims in 2018. That share has since retreated as higher dollar interest rates have attracted investment in US securities, driving up cross-border claims on the United States (grey area).

Offshore use of the euro is small by comparison (Graph 3.B). Inward and outward claims involving euro area residents have long been the largest euro segments, mainly reflecting the euro business of banks in London with counterparties on the continent.6 Offshore positions have accounted for only about a quarter of the total. The rise since 2020 in cross-border positions booked by banks in the euro area (tan area) in part reflects revised reporting of derivatives positions on a gross basis.

Offshore yen claims are smaller still, and their share in total international yen claims has fallen since the GFC (Graph 3.C). The decline in part reflects the contraction, in absolute terms, in the offshore use of the yen since 2008. At the same time, cross-border lending by banks in Japan (tan area) expanded after the GFC as these banks attracted new borrowers with low yen rates. In addition, banks elsewhere have bulked up their claims on borrowers in Japan (grey area). This in part reflected off-balance sheet FX derivatives transactions whereby banks swap dollars for yen and then park the yen proceeds in safe yen assets recorded on the balance sheet (ie the cross-currency basis trade).

For more details download the report – International finance through the lens of BIS statistics: the global reach of currencies

Anders Olofsson – former Head of Payments Finastra

Banking 4.0 – „how was the experience for you”

„So many people are coming here to Bucharest, people that I see and interact on linkedin and now I get the change to meet them in person. It was like being to the Football World Cup but this was the World Cup on linkedin in payments and open banking.”

Many more interesting quotes in the video below: