Tokens and the Economy

An interesting history and even more interesting future of stablecoins presented by David Birch.

Old and New Economies

We are in the middle of the transition from one kind of economy to another (and very different) kind of economy. The new economy needs a different kind of money from that old economy. It needs money that can support the growth of industries in, and economic activities of, the new economy and one of the most important ways it can do this is by using the technologies of the new economy themselves to deliver the money.

As the government has not stepped in to provide this new money so instead technology companies have simply begun to produce their own money. Private money is beginning to circulate. Using the technologies of the new economy, enterprises have started to produce “tokens” that function as money and the market has responded by taking them up and using them as money for the purchase of goods and services and to generally facilitate economic activity.

Tokens have gone from being a limited solution to a specific problem to key elements of the infrastructure in the wider economy and as a consequence the government is now looking at them and wondering how to regulate them, how to manage them and what to do with them in the future.

Welcome to England in 1787.

Tokens Past

England was the birthplace of the industrial revolution as a consequence it was the first economy to see the need for a new kind of money for retail payments. At the dawn of the industrial revolution, the circulating medium of exchange was of neither the quality nor the quantity needed to support the expanding economy. Roger Osborne’s excellent book “Iron, Steam and Money” (Pimlico: 2014) sets out the problems of this mismatch between old money and a new economy:

For the embryonic capitalist industrial system to grow, it needed a banking system to channel investment, while employers needed banks in order to pay their workers. But even on the most basic level of supplying coinage and notes the banking system was, before the mid-eighteenth century, wholly inadequate.

As the currency shortage threatened to derail industrial progress, the new technologists of the day, the new-fangled manufacturers in the newly created factories, began to mint custom-made coins, originally called “tradesman’s tokens”. That practice, of private companies issuing their own tokens, because of a chronic shortage of official small change issued by the Royal Mint, begin in Britain around 1787.

These tokenswhich served as the nation’s most popular currency for wages and retail sales until 1821, when the Crown outlawed all moneys except its own, a story told with exceptional clarity in economist George Selgin’s wonderful book “Good Money: Birmingham Button Makers, the Royal Mint, and the Beginnings of Modern Coinage 1775-1821” which not only examines the crucial role of private coinage in fuelling the first Industrial Revolution but also sheds light on contemporary private-sector alternatives to government-issued money.

Cornish copper halfpennies (1791)

Lessons from History

You may have noticed that the coins and banknotes in your pocket today are produced by the government, not by private players. So what changed? And, more importantly, what can we learn from the change that will give us insight into the future of stablecoins? I’d like to suggest four key areas where the lessons of the Industrial Revolution have some value to the pioneers of the post-industrial Revolution: these are technology, acceptance, finance and regulation as discussed in the following subsections.

Technology

Professor Glyn Davies magisterial “A History of Money from Ancient Times to the Present Day” (University of Wales Press: 1994) makes the point not only did these private tokens fulfil a real need but much of the token coinage was so obviously superior in appearance to the official coinage that the government itself eventually decided that the free market could probably supply copper currency better than could the Royal Mint. Consequently in 1797, Matthew Boulton was given a contract for 50 tons of two-penny and one-penny pieces, accompanied by an Act of Parliament and a Royal Proclamation to place the legality of his new coins beyond doubt.

(You might call Matthew Boulton the Elon Musk of this day in terms of his impact as entrepreneurial catalysts of major industrial transformations!)

By adopting the new technology, the government began to reduce the need for private alternatives. FedCoin, anyone?

Acceptance

Tokens (and later, bank paper money) were created locally and to the degree demanded. Davies again: he notes that this “most useful but unstable volume of credit was being created ‘by the needs of trade’, or in modern terminology, endogenously by the effective demands of business and not exogenously by the central monetary authority”. It was the money of the market, not the Mint. So while private monies were generally trusted and efficient, they could still be subject to doubts about authenticity, weight, and acceptability—especially outside their region of origin.

A single, official coinage—backed by the state’s legal-tender status—eliminated uncertainties and standardized the currency. As the Royal Mint proved it could reliably supply enough coins, there was less economic incentive for merchants and manufacturers to issue their own.

Regulation

Ultimately, the government reasserted its monopoly on coinage. In 1816 (and again in 1817 with regard to copper coinage), Parliament passed laws outlawing the circulation and production of private tokens. The motivation was partly ideological—reasserting state sovereignty over the currency—and partly practical, as the authorities became better able and more willing to supply coinage in sufficient quality and quantity using the new technology

The combination of legal crackdown and credible state action signalled to the public and to the private mints that their era was drawing to a close, which came in 1821 when the government outlawed private monies.

„There’s nothing inherently dodgy about stablecoins. But there is something inherently dodgy about banking, which is why countries build elaborate regulatory regimes to protect deposits.” – Brendan Greely, Financial Times (13th February 2022).

Finance

Finally, there is the issue of finance. By centralizing coin production, the government also kept for itself the “seigniorage” (the profit arising from the difference between a coin’s face value and the cost of production). Private mints eroded this source of revenue. The reassertion of monopoly was, therefore, also a fiscal decision.

Small Change and Big Changes

In summary then, the production and use of these private tokens spread rapidly and soon a great many different issuers, including Big Tech (that is, factories, mines and manufacturers), produced several thousand different designs and types of token. Hundreds of entities became token issuers, a business that pretty much ended in 1797, when the British government responded by officially producing the penny and twopence coins to supply adequate small change while commercial banks grew to provide business-to-business payments.

Tokens Present

In 2024, when the Stripe CEO Patrick Collison labelled stablecoins “room-temperature superconductors” for financial services (after paying $1 billion for Bridge), he was not being hyperbolic and when Stripe went on to buy Privy (which had some 75 million stablecoin wallets out there) in 2025 that sealed the view of stablecoins as mainstream.

Stable Evolution

Globally, stablecoins are on a tear and in almost all cases the cash and assets are the US dollar and dollar securities. The two largest stablecoins out there right now are Tether (USDT; $149 billion) and the USD Coin from Circle (USDC; $62 billion). Circle’s IPO, also last week, saw shares jump as high as $103.75 from the offer price of $31 with heavy investor demand.

Tether and Circle therefore account for some $240 billion in circulation. This is not much in the $36 trillion US Treasury market, but the growth has certainly focused US Treasury’s attention. Why? Well, I agree with Marc Rubenstein’s analysis on this: when I bought my first stablecoin, it was in order to play around in “crypto”. But it is now clear that stablecoins are decoupling from cryptocurrency and their adoption is driven by „practical applications rather than speculation”.

It seems that Stablecoin transactions, broadly speaking, support real world business. For example, Elon Musk’s SpaceX uses stablecoins to repatriate funds from selling Starlink satellites in Argentina and Nigeria, while ScaleAI (the data labelling and AI training company that Meta has bought a 49% stake in for nearly $15 billion) offers its large workforce of overseas contractors the option of being paid this way.

Tokens in 2050

Where do we go next with the new digital tokens of the post-industrial revolution? Noted Fintech investor Matt Harris, a partner at Bain Capital Ventures, predicted that fintech would mean the end of money as we know it. He wrote that rather than money as we know it, in the future „our assets will be 100% invested at all times”. In this apparently radical vision of the future of money, transactions will be settled through the transfer of baskets of assets between counterparties without the intermediary of money. This world, in which assets are constantly on the move, sounds crazy – but Matt is right.

The IBM Dollar

Way back in 1994, I picked up a report from the Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation (CSFI), a London-based think-tank, written by Dr. Edward de Bono, known to many as the inventor of „lateral thinking” and to others as the inventor of the coloured hats for thinking. Dr. de Bono, who his Guardian obituary said was “rarely burdened with humility) passed away this year at the age of 88. Dr. De Bono’s pamphlet had an immediate impact on me, coming as I did from the technology side of electronic payments and money. It was called „The IBM Dollar”.

The heart of the vision that de Bono set out in the pamphlet was that IBM might issue „IBM Dollars” that would be redeemable for IBM products and services, but are also tradable for other companies’ monies or for other assets in a liquid market.

The difference between IBM stock and IBM money, to continue this example, is that IBM stock is a claim on something that is exchanged through intermediaries. But IBM money is, well… money. Or at least, money-like. It is a bearer instrument that can circulate freely until it is used to obtain some service from IBM at which point the IBM Treasury can decide whether to remove it from circulation (ie, burn the token) or put it back into circulation by using it to buy something. The Treasuries of different companies might adopt different approaches to the circulation of their money, different “monetary policies”, as part of their competitive strategies.

Now this apparently strange world of money-like assets in continual motion might at first seem unbearably complex for people to deal with. But that’s not the world that we will be living in. This is not a world of transactions between people but, as I wrote in my book „Before Babylon, Beyond Bitcoin„, transactions between what Jaron Lanier called „economic avatars” and what I lazily call bots.

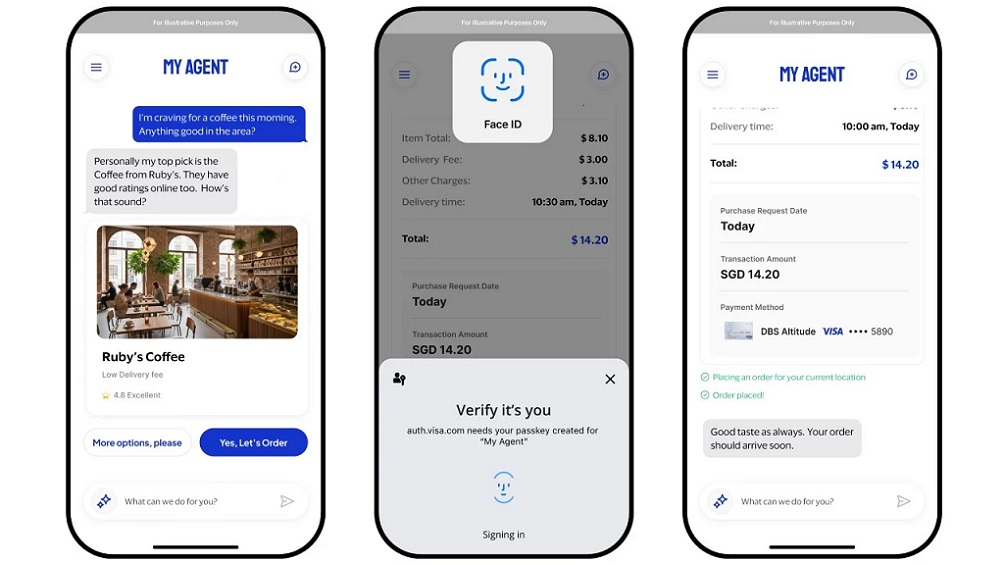

This is a world of transactions between my virtual me and your virtual me, the virtual supermarket and the virtual government. This is my machine-learning AI supercomputer robo-advisor, or more likely my mobile phone front end to such, communicating with your machine-learning AI supercomputer robo-advisor to work out what basket of tokens it wants from you in return for one of my books, or a day of my time at a workshop or a speech to your conference.

Exploring the Transitions

Roger Osborne talks about how the effects of the Industrial Revolution spread far beyond technology and industry. He points out that the entrepreneurs of that new economy in time forced the financial system to change to accommodate their needs. By the time that the private tokens were replaced by a revived public money, the industrialists had built the banking system that they needed. In 1826 Parliament approved the setting up of joint-stock banks owned by shareholders with limited liability. This led to large-scale banks emerging in the industrial cities, a process that culminated when joint-stock banks came into the Clearing House, which allowed cheques to be exchanged between banks.

That period in history, the transition to an industrial economy that is directly comparable in economic shock as the current transition to a post-industrial economy, tells us how new money and new banking systems was pulled into existence by the needs of industry. We can look how that period of creativity and economic growth adumbrates the the coming era agentic business and industry, the coming together of the web3 and digital assets, digital identity and virtual/augmented reality with smart wallets at its heart.

Davis reflects on the transition from the pre-industrial financial world to the new industrial age financial market infrastructure saying:

„This was an unconscious, unplanned and still underestimated transfer of constitutional soverignty; a partial financial democratization that preceded and facilitated the advent of political democracy.„

It must be surely be that case that the new financial infrastructure and institutional arrangements of the post-industrial will similarly facilitate political change. That fact is that both the history and the future of stablecoins are more interesting and more surprising than you think.

Dariusz Mazurkiewicz – CEO at BLIK Polish Payment Standard

Banking 4.0 – „how was the experience for you”

„To be honest I think that Sinaia, your conference, is much better then Davos.”

Many more interesting quotes in the video below: