The centrality of data in the digital economy has enabled the entry into financial services and rapid growth of big tech firms. Big techs have existing businesses in e-commerce and social media, among others, from which they can expand into finance. Their business model revolves around the direct interactions of users and the data generated as an essential by-product of these interactions.

The distinguishing feature of big techs is that they can overcome limits to scale by utilising user data from their existing businesses to scale up rapidly by harnessing the inherent network effects in digital services. In turn, the greater user activity generates yet more data, reinforcing the advantages that come from network effects.

In this way, big techs can establish a substantial presence in financial services very quickly through the so-called “data-networkactivities” (DNA) loop. This gives rise to concerns about the emergence of dominant firms with excessive concentration of market power and a possibly systemic footprint in the financial system.

This Bulletin reviews the policy challenges for central banks and financial regulators in their oversight of the activity of big tech firms in financial services, especially as it relates to the payment system. Traditional demarcations that separate the roles of financial regulators from those of competition authorities and data privacy regulators may become blurred in the case of big techs in finance.

Rules that were formulated with specific financial stability risks in mind (credit and liquidity risk, market risk etc) may be inadequate for addressing the unique combination of policy concerns to which big techs give rise. These concerns bear on the central bank’s core mission to maintain the integrity of the monetary system. In this regard, the central bank should work more closely with competition and data privacy authorities.

Big techs’ growing footprint in the financial system

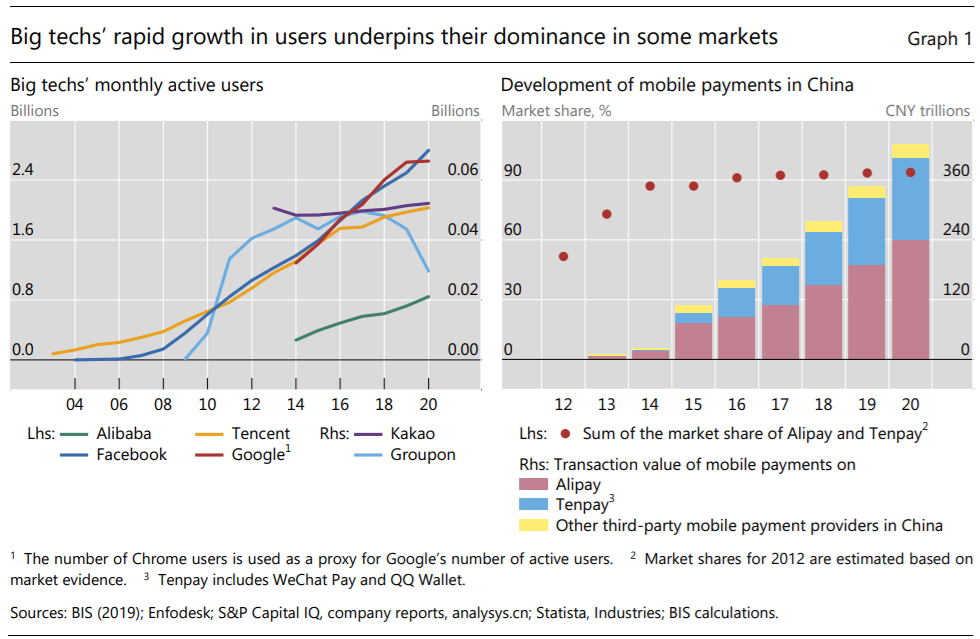

The market for retail payments is a particularly stark example of the potential for rapid concentration. In some jurisdictions, big techs have gained a substantial presence in the retail payment system. For instance, in China the two big tech payment firms jointly account for 94% of the mobile payments market (Graph 1, right-hand panel).

The rapid growth in payment transactions within a few years shows how quickly big tech firms can establish their footprints. Beyond payments, big techs have also become lenders to individuals and small businesses in some markets as well as offering insurance and wealth management services.

Even in those jurisdictions where big techs do not currently have a dominant position in the financial system, their potential for rapid growth warrants close attention from central banks. Stablecoin projects and other big tech initiatives could be a game changer for the monetary system if their entry leads to closed loop systems reinforced by network effects from data drawn from social media or e-commerce platforms. Strong network effects and the entrenchment of closed networks could lead to a fragmentation of payment infrastructures to the detriment of the public good nature of money.

Given the potential for rapid change, the absence of currently dominant platforms should not be a source of comfort for central banks. Rather, they should anticipate developments and formulate policy based on possible scenarios where big tech initiatives may already have reshaped the payment system, instead of focusing on the market structure of the payment system as it currently stands.

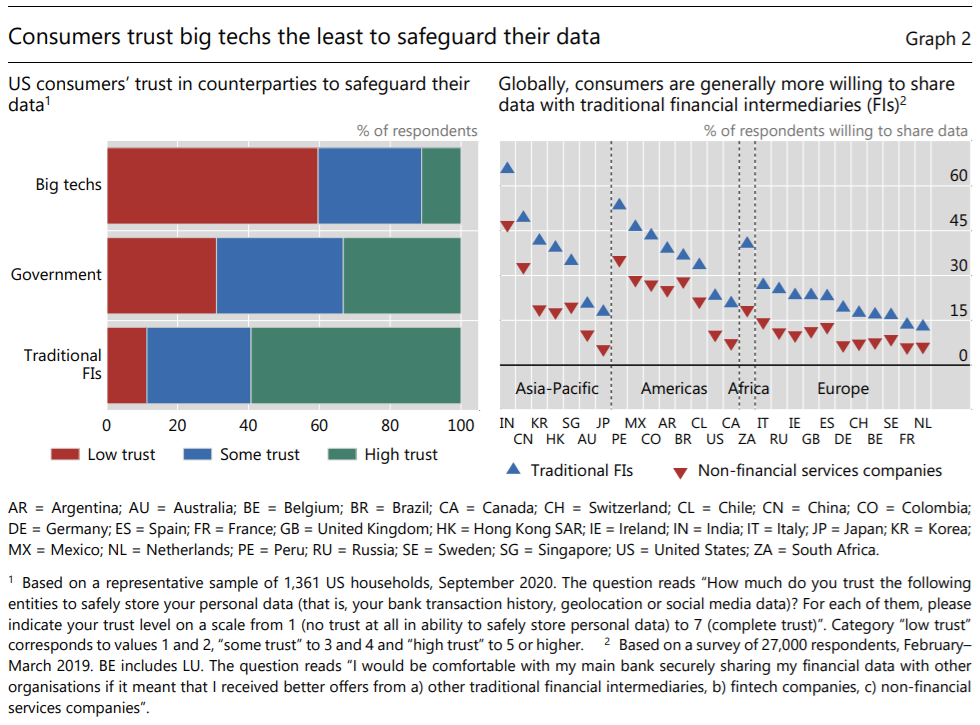

Data governance lies outside the traditional policy scope of central banks. However, as with the competition imperative and the need for dialogue with competition authorities, the entry of big techs into financial services also necessitates close coordination on the part of the central bank with data governance regulators.

Areas where central banks and data governance authorities can usefully contribute their respective analyses include:

Open banking and other data portability rules. Central banks and regulators can assess whether there are asymmetries between banks and big techs regarding data access. They can assess whether differential regulatory treatment of data for different institutions creates competitive, consumer protection or systemic concerns. An example is the requirement in the EU under the revised Payment Services Directive (PSD2) that banks share payment data with big techs. Meanwhile, big techs, under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), need not share their data with banks in a similarly useable format.

Protocols regarding data transfers. Central banks and regulators can assess how barriers to data transfers from domestic regulation or from rules on cross-border data flows (data localisation) may affect the benefits and risks of big techs relative to traditional providers. They can also consider how big techs and traditional providers access personal data in the existing protocols of payment systems, credit registries etc.

Role of public infrastructures. Central banks and regulators can assess how public policy objectives could be attained by public infrastructures that include rules on data governance. For instance, digital identity systems that underlie the design of fast retail payment systems and central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), and associated application programming interfaces (APIs) can be designed to ensure that user control over data translates into effective competition and robust data governance.

Conclusion

The entry of big tech firms into the payment system has underscored how rapidly digital innovation can impinge on central banks’ traditional concerns: sound money and the smooth functioning of the payment system. Given the multi-faceted nature of the public policy challenges that extend to competition and data governance imperatives, central banks and financial regulators should invest with urgency in monitoring and understanding these developments. In this way, they can be prepared to act quickly when needed. Cooperation with other domestic authorities and with counterparts in other jurisdictions will be important in this regard.

Download the document in full: Regulating big techs in finance

Banking 4.0 – „how was the experience for you”

„To be honest I think that Sinaia, your conference, is much better then Davos.”

Many more interesting quotes in the video below: