ING international survey: We’re still suspicious about Open Banking

What we say and what we do when it comes to sharing personal data, notably around Open Banking, are two distinct things. While there are ever more tools to make our financial lives easier, saying we want them and then adopting them don’t always coincide, according to findings from the ING International Survey.

The attitude-behaviour gap

The latest ING International Survey – polling in 13 European countries – finds an attitude-behaviour gap. What people say and what they do when it comes to their finances, doesn’t necessarily align.

In particular, the survey looked at Open Banking – the sharing of financial data between financial service providers with the user’s permission – and at attitudes towards the security of various login systems used with financial apps and websites.

The findings show that sharing personal data and interacting with technology in new ways are not developments that people unanimously support and there are significant differences in attitudes across countries. But many will use tools that rely on these capabilities if they provide them with obvious value.

What we see is a balancing of risk vs reward, and likely a preference for convenience.

Thinking vs doing

These findings do not mean that people are lying or dissembling. They are learning and adapting to a world which is changing at breakneck speed. To paraphrase the American writer and philosopher Elbert Hubbard, some one hundred years ago: „The world is moving so fast these days that the man who says it can’t be done is generally interrupted by someone doing it.” Of course, Hubbard, who died in 1915, didn’t really know „fast”.

It is not even 27 years since the first text message was sent; only 14 since the first touch screen (LG Prada); and 10 since the first investor money was taken by a robo-advisor (Betterment). The past decade alone has seen the widespread adoption of user-friendly tablets, crowdfunding, contactless payments by phone and wearable tech, voice-activated virtual assistants, and the Internet of Things.

Technology adoption is complex. As humans, we gravitate to the tools that work best, inherently a good thing. We judge how they work by the salient benefits we get from them compared with others. Adoption of technology is often powerfully accelerated by network effects, increased use after others have tried it out. Demonstrated social acceptance is also a strong influencer.

But none of these drivers, in themselves, is related to understanding how the tool works. It makes sense for people to say they are staying wary of tech security and of sharing personal information such as their financial data, just in case. But in reality, function is a salient driver of action. Hence people will say they don’t like sharing data but may do so anyway.

This has a name – “the privacy paradox phenomenon”. As Spyros Kokolakis of the University of the Aegean on Samos has said: privacy is a primary concern for citizens in the digital age, but individuals reveal personal information for relatively small rewards.

Fanfare for fintech

Among the newest financial services are apps that rely on data sharing via Open Banking, a function which enables a customer to share their personal financial information with multiple parties, for purposes such as payments, money management or investment.

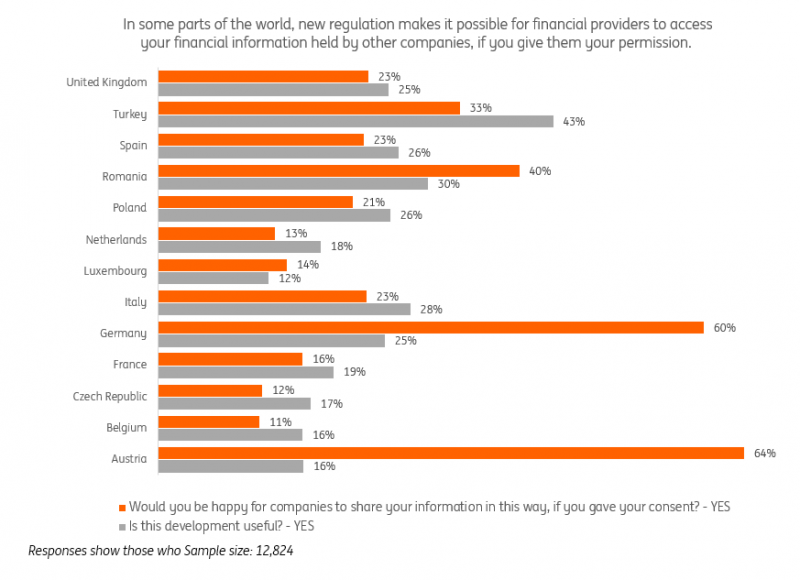

To many people, sharing their finances with organisations other than their most trusted provider sounds scary. Our survey found that only 30% of respondents on average across Europe were comfortable for companies to share their data if they gave consent. That is despite Open Banking being regulated in Europe since 2016 through the EU’s revised payment services directive, or PSD2.

This was also roughly the same percentage as the 35% who said they had heard of the capability. It would have been neat to put the initial scepticism about Open Banking down to the „mere exposure effect” – the psychological concept that simply exposing someone to something increases their positive reaction to it.

But we found that awareness wasn’t driving openness to use or perceptions of value. Those who said they were aware of Open Banking weren’t always the same people who said they thought it was useful.

This demonstrates that awareness of the technical capacity for sharing data isn’t always required for use – other factors are also at work. For example, there were distinct differences in attitudes towards data sharing across countries. In Austria and Germany around two-thirds of people (64% and 60% respectively) were happy for companies to share their information with their consent, while roughly just one in 10 agreed the same in Belgium (11%), the Czech Republic (12%) and the Netherlands (13%).

There was also no clear link between the number of people in a country who agreed developments in data sharing were useful and those who said they would be happy to use the service. Factors such as trust in local providers and cultural attitudes, therefore, are likely also playing a role.

Our findings on sharing information

When it comes to Open Banking, our survey also shows that attitudes haven’t changed much since a year ago but reported usage has. For example, in January 2020 data suggests customer use of Open Banking in Britain, the European leader, surpassed 1 million, doubling over the previous six months. This was despite only 23% of Britons in our survey saying they would be happy sharing information this way.

Another reason for this may be opportunity and familiarity. There are 178 firms in Britain that are permitted to provide account information or payments via third parties. Germany comes in a distant second with 36, a number that is greater than that for France (18), Spain (9) and Italy (6) combined.

It is early days for the sector, of course, and some places may be gearing up for a big jump. Germans, for example, have a strong tradition of trust when it comes to banking and some 60% of our German respondents said they would be happy for their banks to share their account information.

„Open access to financial data using API technology is relatively new, but it has triggered considerable changes to the way financial service providers think about their banking ecosystem and the products within it. Open Banking may lead to increased partnerships and innovative products, empowering consumers to make decisions around how they use and share their personal data”. – Maciej Kostro, Global Principle Product Owner, ING.

In the end it may just come down to convenience and trust. The benefits of Open Banking, such as quickly tracking finances and moving assets around from one interface are quite easy to see. Trust, though, is more complicated, relating to attitudes towards both the institutions involved and the security of accessing data. And calculating the value of sharing one’s individual data is complex.

Convenience is key

UK polling firm Ipsos has found strong evidence of a disparity between what people say they want and what they say they are prepared to do. One of the firm’s surveys found 75% of people would like to have access to data on how they spend their money, but only 40% said they were comfortable providing the information that could lead to that.

So, what do people consider secure? With pretty much everyone owning a smartphone these days, (26% of our survey respondents say they have an iPhone and an additional three quarters (73%) own an android smartphone), people have access to a plethora of security systems. These range from simple passwords to voice, face and fingerprint recognition or a combination of them.

The value of the global fingerprint-sensor market, for example, is expected to rise to $5.2 billion in 2026 from today’s $2.9 billion, partly as a result of the increasing numbers of smartphone, tablets and wearable devices taking on the security system.

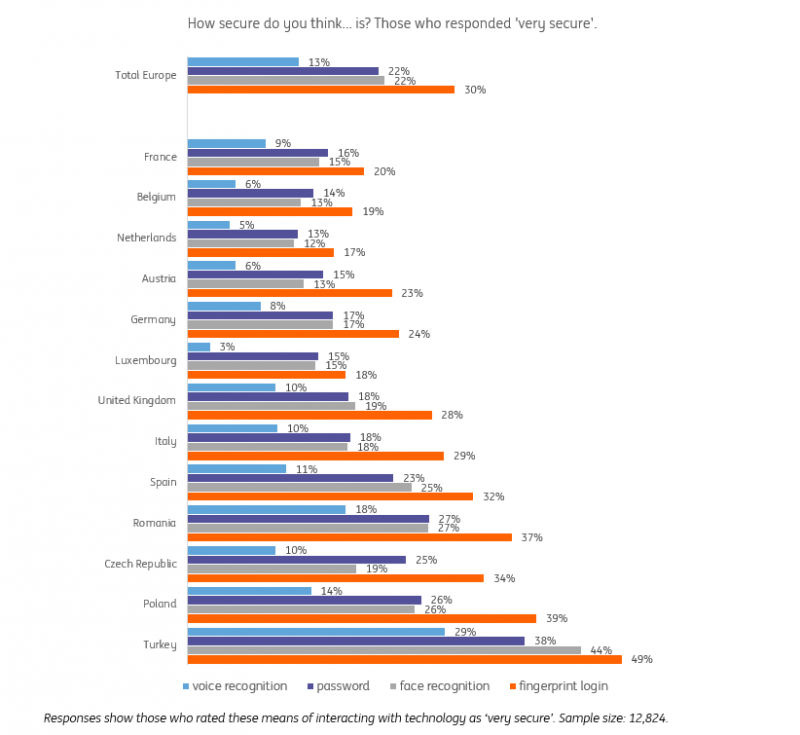

Yet, only a third (30%) of Europeans in our survey said fingerprint logins are „very secure”. And this was one of the top-rated systems for security: only 22% said face-recognition was „very secure” and just 13% said it of voice recognition.

And again, we saw clear country differences. The French, Belgians and Dutch were generally the least happy about security, while the Turks, Czechs, Poles and Romanians were somewhat more trusting. But even in those countries, fewer than half of respondents said the various security systems were “very secure”.

Our findings on security

The behavioural implication

The percentages of people at the other end of the scale, those who said these systems were „not secure at all”, were fairly small. But there was little change in attitudes between our findings on this issue in 2019 and now, despite rapid uptake.

The behavioural implication of all this is that there are people using this technology or expected to start using it who remain wary of it. This once again suggests that utility and/or reward is a driver of adoption, and will overcome concern in the right circumstances, for some users.

So there is hesitancy, yes. But trust in providers, rewards, short-term needs, familiarity and even what we see our friends doing, may all conquer suspicions. As technology continues to expand, however, the gap between what people say and what they do is unlikely to go away.

Dariusz Mazurkiewicz – CEO at BLIK Polish Payment Standard

Banking 4.0 – „how was the experience for you”

„To be honest I think that Sinaia, your conference, is much better then Davos.”

Many more interesting quotes in the video below: