Gatekeeping the gatekeepers: when big techs and fintechs own banks – benefits, risks and policy options

The Financial Stability Institute (FSI) of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) – a report by Raihan Zamil and Aidan Lawson

Over the past decade, big techs and fintechs began to provide a range of financial services to consumers, initially outside the confines of the highly regulated banking industry. These services started with payments, but expanded to encompass consumer lending, insurance and wealth management. In their provision of financial services, some big techs and fintechs compete directly with banks, while others work in partnership with them through various arrangements, to fulfil their customers’ banking needs. From the perspective of big techs and fintechs, the main benefit of providing bank-like financial services without a banking licence is the limited regulatory oversight, which allows them to focus on enhancing their technology, improving product offerings and enriching the customer experience.

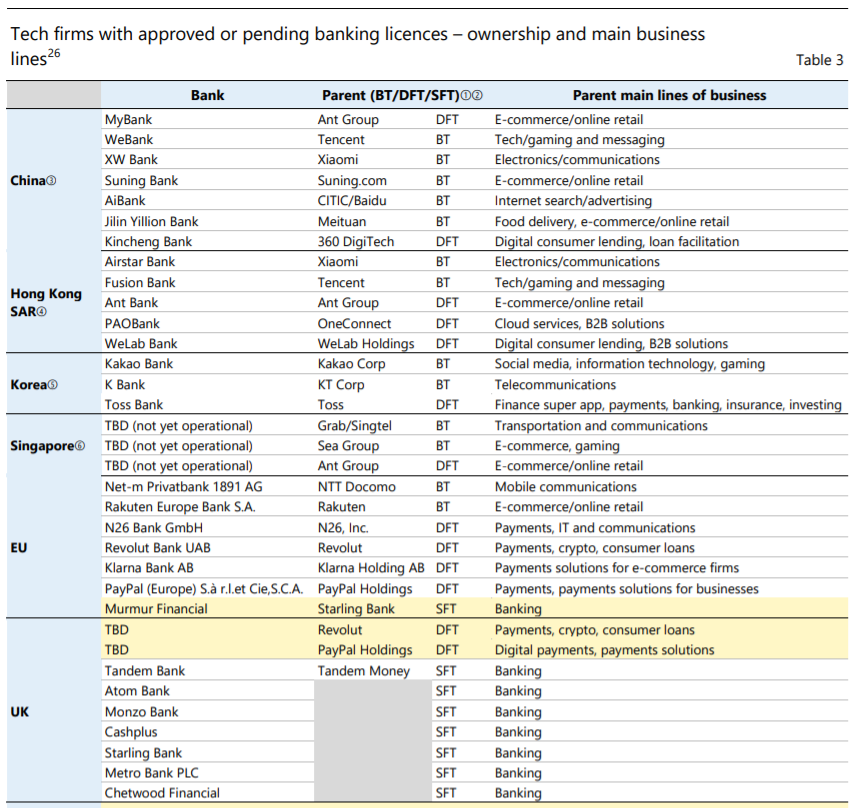

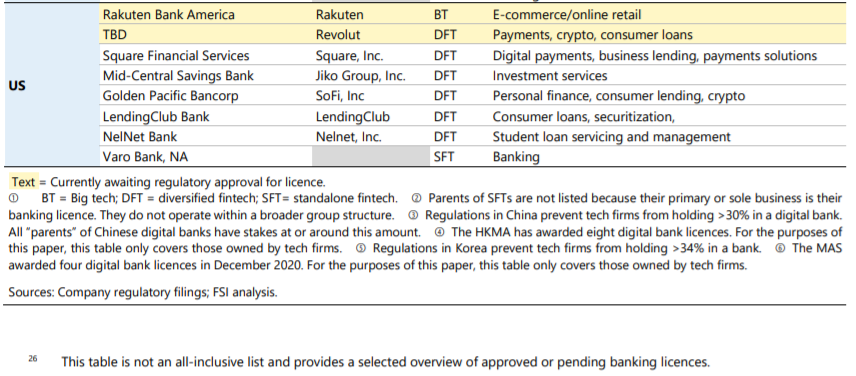

More recently, several big techs and fintechs have obtained a banking licence in various jurisdictions. Despite the regulatory scrutiny that accompanies a banking licence, a number of big techs and fintechs see the value proposition that it confers. Asia, and in particular China, is home to the largest number of big techs that operate with a banking licence. Numerous fintechs have also been granted bank charters in the United Kingdom and to a lesser extent in the European Union (EU) and the United States. Access to low-cost deposits that complement their product offerings, the cost savings associated with eliminating the need for partner banks, the perceived trust and legitimacy that a banking licence bestows and the possibility that investors may reward such firms through higher market valuations more than offset the costs associated with operating as a bank.

These developments have been facilitated by an enabling regulatory environment. Despite historical concerns regarding the ownership of banks by non-financial companies (NFCs), several banking authorities – particularly those with objectives that encompass financial inclusion and/or competition – have allowed technology firms to own banks. This shift in approach reflects their view that technological innovations in the provision of financial services may help to improve consumer outcomes. Several Asian jurisdictions have introduced digital bank licences, while others (UK) have streamlined their licensing process or expressed an openness to consider tech firms to obtain a banking licence (EU and US).

This paper assesses the benefits and risks of extending banking licences to big techs and fintechs. The findings are based on publicly available information on applicable licensing requirements in seven jurisdictions covering Asia, Europe and North America. A key focus of the paper is to compare the merits of bank ownership by tech firms in relation to ownership by commercial or industrial NFCs.

To help differentiate their risk characteristics, this paper classifies tech firms into three distinct groups: (i) standalone fintechs whose financial activities are conducted solely or primarily through their banking entity; (ii) large diversified fintechs which engage in a broader range of (mainly) financial services through various channels, including the parent entity level, their subsidiary bank and other non-bank subsidiaries, joint ventures and affiliates; and (iii) big techs with core non-financial businesses in social media, internet search, software, online retail and telecoms, who also offer financial services as a secondary business line.

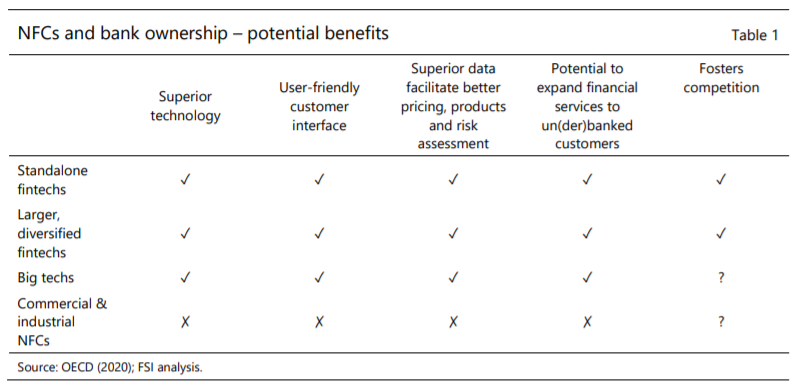

The perceived benefits of allowing tech firms to operate with a banking licence are compelling, but require scrutiny. Unburdened by legacy infrastructure, tech firms often offer superior technology and user-friendly apps that may allow them to reach more consumers and perform various aspects of the banking business (onboarding, deposit-taking, lending, payments) more efficiently than incumbents, including commercial or industrial NFCs that may own banks. Collectively, their technologycentric approach in the delivery of financial services is expected to advance some authorities’ broader goals of fostering financial inclusion, promoting competition and delivering better outcomes for society. Nevertheless, as part of the authorisation process – and subsequently through ongoing supervision – authorities need to examine the ability and willingness of tech firms to deliver on their stated objectives.

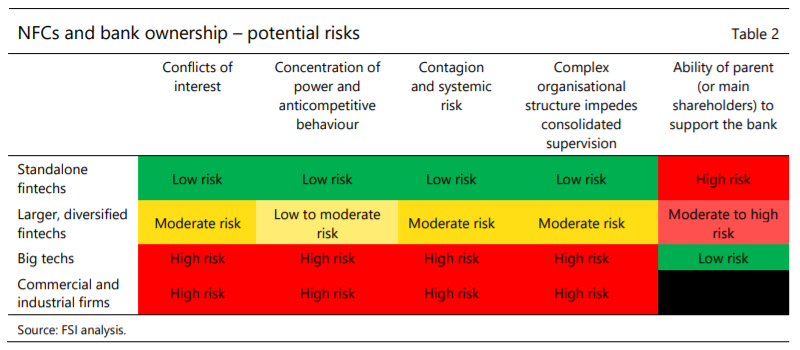

The inherent risks, however, differ markedly across tech firms, with big techs posing the greatest challenges. To ascertain the underlying risks of bank ownership, we map five key risk factors across the three groups of tech firms specified in this paper. The first four factors – conflicts of interest, concentration of power/anticompetitive behaviour, contagion and systemic risk, and impediments to consolidated supervision – are specific concerns that are typically cited when commercial or industrial NFCs seek to own banks, and thus can also be applied to tech firms that own or are seeking a banking licence. The fifth factor, the ability of the parent or shareholders to support the bank in times of need, is a key element of the licensing process in all authorities. In aggregate, the risk profile of big techs, particularly across the first four factors, pose the highest risks among tech firms, followed by large, diversified fintechs.

Authorities impose a range of financial and non-financial requirements as a precondition for tech firms to operate a licensed bank. Three critical provisions include the imposition of a financial holding company (FHC) structure to house tech firms’ various financial activities to facilitate consolidated oversight (China and Hong Kong SAR); the application of higher risk-based capital requirements on digital banks, due their untested business models (Singapore) or the imposition of higher leverage capital ratios to tech-owned banks in relation to traditional bank startups (US); and bank ownership limits on NFCs, including more severe caps for any company that violates anti-monopoly rules (Korea). To assess the parent’s ability to support the bank, China requires the tech-owned parent of the FHC to be profitable for at least two consecutive years, while the US requires the parent (if it is an NFC) to pledge assets or to secure a line of credit to demonstrate its source of strength. Key non-financial provisions include prior technology experience of bank sponsors; limitations on overlapping boards and shared officers between the bank and (the tech) parent to minimise conflicts of interest; prohibition of predatory tactics used to gain market share; and a provision to develop an exit plan in case the bank fails.

In devising licensing requirements, authorities should consider the inherent risks posed by tech firms. Among the three groups, the risk characteristics of big techs and large diversified fintechs pose the biggest supervisory concerns, with the former likely to require more onerous requirements than the latter. While standalone fintechs present lower overall risks, they have less flexibility – in relation to other tech firms – to provide financial support to their banking entity if needed, which should be considered during the authorisation process. In this context, various aspects of the licensing regime can be tailored for and adapted to tech firms’ unique risk profiles to mitigate the underlying risks, but supervision and enforcement may pose formidable challenges.

The question of whether to allow tech firms to operate with a banking licence has the potential to permanently alter the landscape of national banking systems. Prudential authorities, as gatekeepers of the banking system, must decide whether to allow entry to these new gatekeepers of the digital economy and, if so, what requirements to impose on them. At one end of the spectrum is prohibiting or creating formidable barriers, while at the other is developing an enabling regulatory environment to facilitate their entry. The space between these theoretical extremes provides scope for prudential authorities to consider policy trade-offs that are appropriate for their jurisdiction-specific circumstances.

pdf – full text – Gatekeeping the gatekeepers: when big techs and fintechs own banks – benefits, risks and policy options

Dariusz Mazurkiewicz – CEO at BLIK Polish Payment Standard

Banking 4.0 – „how was the experience for you”

„To be honest I think that Sinaia, your conference, is much better then Davos.”

Many more interesting quotes in the video below: